The Hype: Done.ma, ORA Technologies and Morocco’s Super App fever

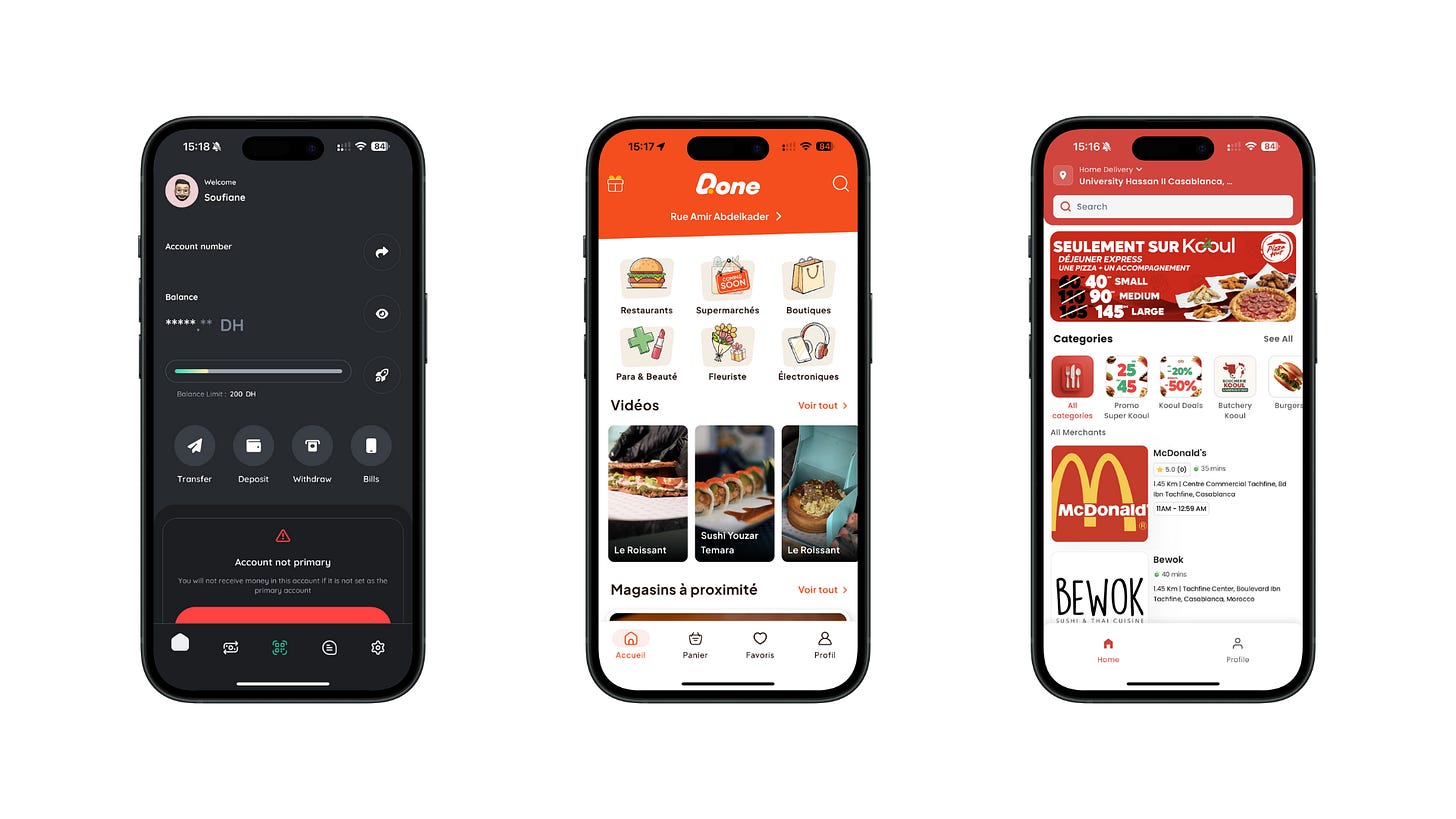

During the last few weeks in Rabat, the founders of Done.ma unveiled what they proudly called “Morocco’s first super app.” In one platform, Done promises to handle everything “from food to shopping and various services”, as one excited launch announcement put it. The buzz is real: local tech circles have been eager to see a homegrown “app of apps” that can do it all, inspired by the WeChats and Gojeks of the world. Done’s launch follows a broader trend in Morocco – and Africa at large – where startups are racing to label themselves super apps. Another Moroccan startup, ORA, recently raised funding to build a similar all-in-one platform, touting features ranging from peer payments and e-commerce to social networking, all inside one app. Enthusiasm for this model is palpable, and it’s easy to see why: who wouldn’t want to be the digital hub of their users' daily lives?

Yet amid the fanfare, a crucial question lingers: Are these startups putting the cart before the horse? History suggests that the most successful super apps did not start out trying to be super apps at all. And that might be where many Moroccan aspirants are getting it wrong. Before we dive headlong into the super app gold rush, it’s worth examining how the giants of the genre actually got to be so “super.” Spoiler: it wasn’t by doing everything from day one :)

Big Super Apps started small (really really small)

Think of any tech giant known as a super app today, and trace its origins. A striking pattern always emerges: they began with a razor-sharp focus on a single, high-utility service, earned user trust and high engagement there, and only then methodically expanded into new offerings and services. A few examples illustrate this focus-first strategy:

WeChat (China) – In 2011, WeChat launched simply as a mobile messaging app, akin to WhatsApp. No payments, no games, no shopping – just chat. It gained hundreds of millions of users on the back of that core messaging experience. Only later did Tencent layer in payments (WeChat Pay came in 2013), and then a plethora of mini-apps and services. By not trying to be “everything” upfront, WeChat first became the default daily communication tool for a billion users. That gave it the primacy of user relationship needed to introduce payments, shopping, ride-hailing, and more without users blinking. (Fun fact: after WeChat added its wallet feature in 2013, its user base surged to 400 million within a year – a testament to how a trusted core app can quickly convert users to new services.)

Gojek (Indonesia) – Gojek’s story starts not with an all-purpose app, but with ojeks (motorcycle taxis). In 2010 it was a humble call center for ordering bike rides. When it launched a smartphone app in 2015, it offered just a few related services (ride-hailing, courier delivery, food delivery) to solve everyday transport and logistics needs. Crucially, all those services leveraged the same core asset: a network of drivers. Only after Gojek became synonymous with getting around Jakarta did it branch out. Fast forward, Gojek transformed into a true super app with 20+ services from massages to digital payments, and amassed about 170 million users in Southeast Asia by 2020. The key was that each new service piggybacked on a platform that users were already opening daily for rides and deliveries.

Grab (Southeast Asia) – Similarly, Grab started in 2012 as MyTeksi, a simple taxi-hailing app in Malaysia. It solved a specific local problem (unsafe, unreliable taxis) with a mobile solution. Over years, Grab expanded stepwise – private cars, then food delivery, then fintech – effectively earning permission from users to move into new domains. Today, Grab is a NASDAQ-listed super app operating in eight countries and valued in the tens of billions, but its origin was nothing more complicated than booking a cab. As Emeka Ajene article noted, unlike WeChat’s messaging roots, “Gojek & Grab both offer ride-hailing as their core service and have become ‘must-own’ apps” largely because public transport in their markets was underdeveloped. In other words, they nailed a high-frequency, high-friction use case “ daily transportation “ before attempting to conquer other verticals.

Paytm (India) – Now one of India’s prominent super apps, Paytm didn’t burst onto the scene doing 50 things. It launched in 2010 as a mobile recharge service, a simple wallet to top up prepaid phone credits. This was a frequent need in a country where most people’s phones were prepaid. Once Paytm became a verb for recharging (“Paytm karo” became slang for “make a payment”), it gradually expanded into bill payments, e-commerce, movie tickets, banking, investments, you name it. A decade on, that single-use-case start blossomed into an app offering “a thousand plus” services in payments, commerce, and finance to over 333 million consumers and 21 million merchants. It’s a classic case of land and expand: land with a narrow service that hooks users, then expand into their adjacent needs. Paytm’s massive user base was built on trust earned from something as mundane as phone bills.

The are many other example around the world, Alipay began as an escrow payments service for Alibaba’s e-commerce site. Meituan in China started with group-buy deals before becoming a catch-all lifestyle app. The pattern is so consistent it’s almost a playbook: get users to rely on you for one thing first. In short, focus bred loyalty, and loyalty became the foundation for expansion.

Why focus first matters (especially in emerging markets)

If you think the stories above sound far removed from Morocco, think again. The underlying logic “start with a high-frequency, high-utility wedge“ is even more critical in emerging markets like Morocco. Here’s why a focus-first strategy isn’t just a nice ideal but a practical necessity:

1. Trust is hard to earn (and easy to lose). In markets where many consumers are coming online for the first time or are generally skeptical of digital services, trust is everything. A new startup asking users to do ten different things in one app, from hailing rides to storing money to ordering groceries, is asking for an enormous leap of faith. Users will hesitate: Is this app really good at any of these services? It’s far easier to convince someone to try you for a single service that clearly meets an immediate need. Deliver on that promise exceptionally well: a hot meal delivered fast, or a safe ride home at 2 AM, or a seamless bill payment → and you’ve built a reservoir of trust. That user is now much more likely to try your second service. But if you fumble any one of the many promises a super app makes early on (late deliveries, glitchy payments, etc.), you sour their perception of the whole platform. Focus acts as a quality filter: it forces you to nail the experience. It’s no coincidence that WeChat’s meteoric rise in engagement came after years of perfecting chat, or that Gojek’s brand was built on reliable rides. In Morocco, a focused app can more quickly become synonymous with quality in one domain, a reputation that can later carry over to other domains. I had the privilege of launching Glovo and witnessing its rapid scale in Morocco. If there was one core obsession that guided us, it was becoming the go-to app for anything you needed delivered: fast and reliably.

2. Customer acquisition costs (CAC) are sky-high when you’re doing everything. Each service in a super app is essentially a mini-business with its own economics and user acquisition channels. Acquiring a user who wants food delivery is different from acquiring one looking for a loan. Giants like Grab and Gojek could spend billions to cross-subsidize and promote multiple services, but a Moroccan startup as of today (hopefully it changes soon) isn’t sitting on that kind of war chest. It’s far more efficient to win a narrow customer segment deeply than to scratch the surface of many segments. For example, if you become the go-to app for, say, ordering lunch in Casablanca’s business district, you can gain a critical mass of engaged users relatively cheaply (perhaps via word-of-mouth and targeted marketing in that niche). With that user base in hand, layering a new offering (maybe a grocery service in the evenings) has a much lower CAC, you’re marketing to existing users in your app for “free.” On the flip side, launching with six mediocre services means six different marketing campaigns and a diluted value proposition (“We do everything, kind of okay” doesn’t convert). iFood founder once said that if you layer a mediocre service into your app, the churn in your core service will be impacted and hence you impact negativity the whole customer experience. In a resource-constrained startup environment, focus is and will always be your friend.

3. Infrastructure and operations are limiting factors. Let’s face it: executing even one of these services is hard. To do food delivery at scale, you need drivers, restaurants, strong algorithms, customer support and a ton of money. To do payments, you face integrations with banks, regulators, and agent networks for cash in/out. To do e-commerce, you need inventory or seller onboarding and reliable shipping. Now imagine trying to build all of that simultaneously as a startup. It’s a recipe for broken systems and burnt cash. Many African super apps have learned this the hard way. OPay in Nigeria tried to juggle ride-hailing, food delivery, a bus service, and even a tricycle taxi service alongside its payments business. The result? Within two years, it had to shut down or “pause” its transport and logistics offerings (OBus, ORide, OCar, OExpress) and refocus purely on its fintech core. The company cited harsh conditions (regulatory bans on bike taxis, COVID-19, etc.), but the underlying issue was trying to do too much too soon. In contrast, the one part of OPay that truly broke out was its mobile money service, which had always been its primary play. The moral: each additional service is not just a software feature, it’s an operational beast. Morocco’s infrastructure (from courier networks to digital payment rails) is improving, but still presents enough challenges that a startup would be wise to tackle them one at a time.

4. The user experience can suffer. Super apps promise convenience, one login, one interface for everything. But if not executed well, they can become jack-of-all-trades, master-of-none platforms that frustrate users. Imagine an app where the food ordering section has limited restaurants because the team also spent time building a mediocre shopping section with limited stores, and a half-baked chat feature no one uses. A savvy user will simply stick to the dedicated food app or the dedicated chat app that does it better. This is a real risk!! If Moroccan super apps bombard new users with a buffet of half-ready services, they may end up using none. Onboarding flows, UI design, customer support, all these have to scale with complexity. Many of Morocco's new internet users might not have high-end phones or unlimited data, a bloated app trying to load dozens of features could literally perform poorly on their devices. A lean, focused app avoids becoming a UX swamp.

All these factors boil down to one principle: earn the right to expand. You don’t get to be a super app just by deciding to bundle many services together: “you gain the right to be a super-app by first gaining primacy of the user relationship through a core use case”. In plain terms, do one thing so well that users keep coming back, and only then do you have a shot at successfully offering them a second, third, or tenth thing.

The Moroccan context: Hard truths and Opportunities

It’s worth noting that the super app craze in Morocco isn’t happening in a vacuum. Across Africa, entrepreneurs have been eyeing the successes of Asia’s super apps and asking “why not here?” Following the Chinese examples, many African startups have launched with ambitions to replicate the super app model. A few examples are Gozem in West Africa, SafeBoda in East Africa, and Yassir in North Africa, all are in the game, trying to bundle services from transport to payments. The investor dollars behind them suggests there is real appetite for all-in-one platforms on the continent. After all, Africa’s digital boom is fueled by a young, mobile-first population and increasing internet connectivity, a fertile ground for super apps.

But the same context presents unique challenges. Fragmented regulation, cash-based economies, and the dominance of global incumbents in certain verticals (hello, WhatsApp and Facebook) mean a copy-paste of the Asian super app playbook is not straightforward. Take messaging, for instance. WeChat could start as a messaging app in China partly because there was no entrenched alternative at the time. In Morocco (and virtually all of Africa), WhatsApp is already the default messenger. A startup that dreams of being a WeChat-like super app via messaging is probably dreaming, detroning an app used by literally everyone is a fool’s errand. This is why most African super apps choose a different wedge: often ride-hailing or payments, where there’s still white space or unmet demand.

The Moroccan market itself has some clear “wedge” opportunities if one looks closely at local needs and pain points. Understanding these can point the way to a smarter super app strategy, one that starts focused on solving a real problem before expanding. For me, a few potential wedges stand out:

Digital Payments & Financial Inclusion: Morocco, like many African markets, has a large population of unbanked or underbanked citizens. Cash remains king. A trustworthy, easy-to-use mobile wallet could be a game-changer as a foundational service. This might mean enabling peer-to-peer transfers, bill payments, or mobile phone top-ups digitally, these are services with nearly universal demand. A super app that first becomes the way people send money to family, receive remittances from abroad, or pay utility bills could quickly become a daily habit. Once you’re managing someone’s money flows, you’ve earned a huge amount of trust, and you can leverage that to offer commerce, loans, or any number of services. Put simply, fintech can be the anchor, few players are already very well positioned for this (think of CashPlus). For Moroccan startups, focusing on a payments wallet or mobile banking service might be the most potent entry strategy, setting the stage for a broader platform down the line (but again stay focused and do not try to do everything at the same time).

Urban Mobility or Delivery Logistics: Morocco’s cities are modernizing fast, but transportation and delivery infrastructure haven’t fully caught up. Ride-hailing faced setbacks (Uber’s rocky exit in 2018 is well-known, though its subsidiary Careem still operates and they recently announced their comeback to the country!) due to regulatory friction. Still, solving urban mobility remains a massive opportunity! (Hello World Cup 2030). A startup that can lawfully and reliably move people in cities like Casablanca or Marrakech would fill a real gap. Daily commutes are a high-frequency need, crack that, and users will happily check your app multiple times a day. If not people, then goods: the rise of e-commerce in Morocco means there’s growing demand for efficient last-mile delivery. A focused service on fast, affordable delivery could become indispensable to a segment of users, the best example for this is Glovo, wherever you go now food delivery in the country is linked with the Glovo brand. How did they do it? well as we said a single-service focus always wins mindshare. Still, a word of caution here: logistics is operationally heavy, so whichever slice (people or packages) a startup picks, it should double down on doing that better than anyone (faster pickups, better coverage, better prices) rather than prematurely launching ten services. There’s a reason Gojek and Grab started with rides, it allowed them to build driver networks and routing tech that later powered food and parcel deliveries. Moroccan super app aspirants could follow a similar path: build the network first with one service, then extend its use.

Hyper-Local Services with Cultural Fit: Another angle is to focus on a service that taps into specifically Moroccan habits and then expand outward. For example, a super app might start by being the go-to platform for hiring local domestic help (cleaners, handymen) in a country where these services are often sourced informally. Or perhaps a focus on marketplace for local goods, imagine an app that first becomes known as the place to buy and sell traditional Moroccan crafts or argan oil products, building a community of buyers/sellers, then later adding more categories. The initial user base might be smaller than something like payments, but passionate. Once you have that niche, you can grow horizontally. The key is that initial vertical should be something with high engagement and a local twist that global competitors aren’t already dominating. Think of how Bukalapak in Indonesia (not exactly a super app, but instructive) focused on digitizing mom-and-pop shops, or how Careem in the Middle East introduced local features like scheduling car rides for prayer times. In Morocco, culture-specific insights could reveal a unique wedge that’s not obvious from the outside.

Avoiding the “All-In-One” trap

The vision of a super app is undeniably attractive: if you succeed, you become a gatekeeper of the digital economy, touching every transaction. But trying to launch as a super app on day one is like trying to be a decathlete before you can run a 5K. As we’ve explored, the global champions earned their stripes by starting with a singular focus. They reached what we call product-market fit in one area, and only then did they leverage that position to expand. In the words of Samora: the focus on solving real-world, everyday services first is what sets up a super app for success in emerging markets. It’s after you’ve won the morning (perhaps by getting someone to commute with your service daily) that you can win the afternoon (by delivering their lunch) and the evening (by being their mobile bank).

For Moroccan founders and investors fascinated with the super app concept, here’s a grounded playbook to consider:

Pick your battle wisely: Identify a service that is frequent, high-need, and currently underserved. One test is to ask: will users potentially open this app daily or weekly for this one thing? If not, keep iterating on the concept. The super apps that thrive are the ones users habitually use. If the initial use case is too niche or infrequent (buying concert tickets, for example), it won’t give you the engagement needed to expand into other services.

Be the best at that one thing: This can’t be overstated. Your version 1.0 needs to absolutely delight users in the core service. That means outdoing any single-vertical competitors on their turf. If it’s food delivery, offer the fastest delivery or best selection in your launch city. If it’s payments, make it the simplest, lowest-fee experience around. Early user love will translate into organic growth, and stories you can tell when you introduce feature #2 or #3 down the line. In contrast, a lukewarm reception to a do-it-all app is hard to recover from, users will have labeled you “so-so” and moved on.

Leverage cross-service synergies, but one at a time: Once you have that loyal user base for Service A, design your expansion to Service B in a way that adds value rather than distracts. The expansions that work often make the original service even stickier. For instance, when WeChat added payments, it supercharged the chat experience, suddenly you could send money to friends in a message. When Grab added food delivery, it gave their drivers more jobs (lowering wait times) and gave riders a new reason to open the app at meal times. The idea is to layer services in a way that they reinforce each other, not just coexist under one roof.

Scale operations in step with offerings: A super app isn’t just an interface, it’s an ops machine. Ensure that before you launch Service B, Service A’s operational backbone is solid and maybe even able to support B. For example, if you have a fleet of couriers doing restaurant deliveries, that could be extended to pharmacy deliveries or document couriers without starting from scratch. The lesson here is: don’t hesitate to focus on what’s working and hold off on what’s not. You can always launch new services later, but if you burn user goodwill early, you might not get “a later”.

Conclusion: The Long Game for Morocco’s Super Apps

The dream of building “Morocco’s WeChat” or “Africa’s Grab” is a compelling one, and not impossible. The country’s demographics and digital trajectory mean that one day, an all-in-one app could indeed become the central hub of people’s digital lives. But the path to that summit isn’t a straight line, it’s a stepwise climb. The first generation of super app aspirants in Morocco have the unenviable task of being both pioneers and guinea pigs. They will shape how consumers perceive super apps, and by extension, they carry the responsibility to get the model right.

The early signs suggest a need for course correction. Done.ma’s launch fanfare about doing everything or ORA’s rapid expansion into multiple services might need to give way to a more grounded narrative of doing one thing well to start. This isn’t a setback, it’s simply stage-appropriate strategy. Consider it a chapter in the lean startup ethos: do things that don’t scale, until they do. In this context, “not scaling” means perhaps not scaling your scope too wide too fast. It’s entirely plausible that the incoming players find their groove in one vertical, say, dominating food delivery or payments, and that becomes the cornerstone of a future super app empire. The founders just have to be patient and disciplined enough to follow that playbook rather than chase the super app label prematurely.

There’s also a role for investors and ecosystem supporters here. Rather than push startups to pitch themselves as “the next super app” from the outset (because it sounds sexy), they should encourage focus and measure success by engagement depth, not breadth of features. The irony is, if you focus on depth first, breadth often follows naturally. If you focus on breadth first, you might achieve neither.

Morocco is at an exciting juncture. The ingredients for big tech successes are coming into place: talent, capital, market hunger. A Moroccan super app that truly wins users’ hearts and minds will likely emerge in the coming years. But it will emerge not as an overstuffed super app at birth, rather as a generalist that earned its credentials as a specialist initially. The super apps of tomorrow may very well rise from the single-purpose apps of today.

So, to all the ambitious builders in Casablanca, Rabat, and beyond: dream of the super app, yes, but start by building a super app (small “s”, small “a”) a superb application for one essential service. Nail that, and you’ll have all the momentum (and user trust) you need to layer on the rest. After all, the pyramids of Giza weren’t built by trying to place the capstone first, they were built brick by brick, level by level, and stand the test of millennia. Morocco’s digital pyramids should be no different.

Have fun!

See you in the next one!

Thanks! Doing better than professional journalists at covering a key topic. Am willing to bet the bank that these apps will have disappeared in a short time